The Californians

On the most recent episode of Accidental Tech Podcast, Marco Arment described a recent ordeal with a moving truck. He recounted his list of grievances from using a rented box truck in New York, and mentioned the issue of roads that trucks aren’t allowed on, or won’t fit on. New York parkways (park on the drive way, yeah, yeah we all know the joke) apparently don’t allow trucks. The major mapping applications he mentions - Google Maps, Apple Maps, Waze - don’t have a feature to avoid roadways that don’t allow trucks, as they do for avoiding tolls.

He used two crappy apps that offered truck routing, but both were poor quality and he lamented that this isn’t just a feature of Apple Maps, Google Maps, or Waze.

Then John Siracusa joked about how this is because Apple’s based in California. “I don’t even know if they have toll roads in California. If you live in California please don’t tell me you don’t have toll roads, I don’t want to know.”

We have freeways which have free in the name because the West Coast was very pro-car after WWII. There are very few toll roads, because then they wouldn’t be free ways, and the unfortunate use of free influences a lot of our infrastructure. With only High Occupancy Vehicle lanes, and HOV stickers for some EVs to try and shape all that free, bumper to bumper traffic.

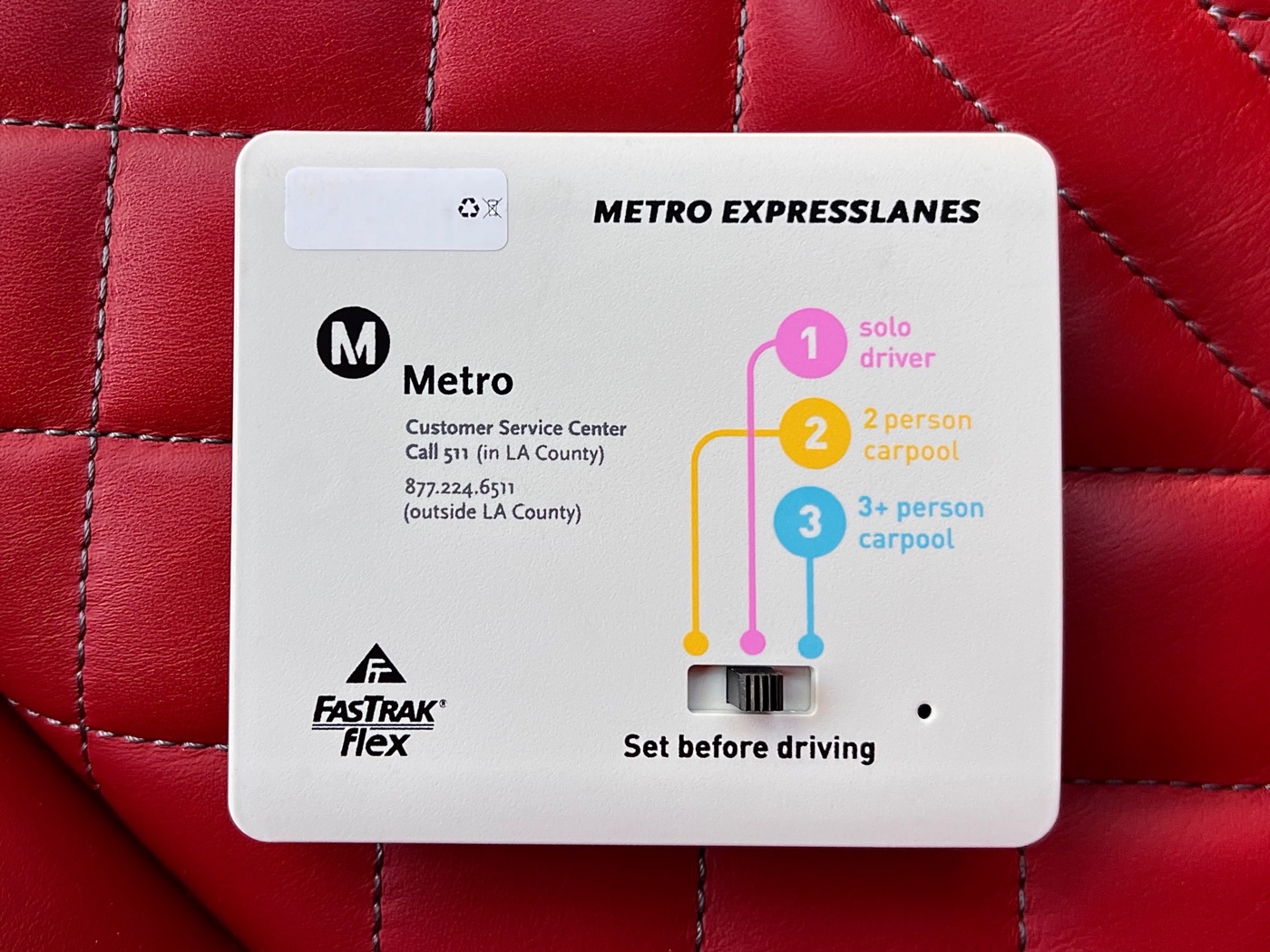

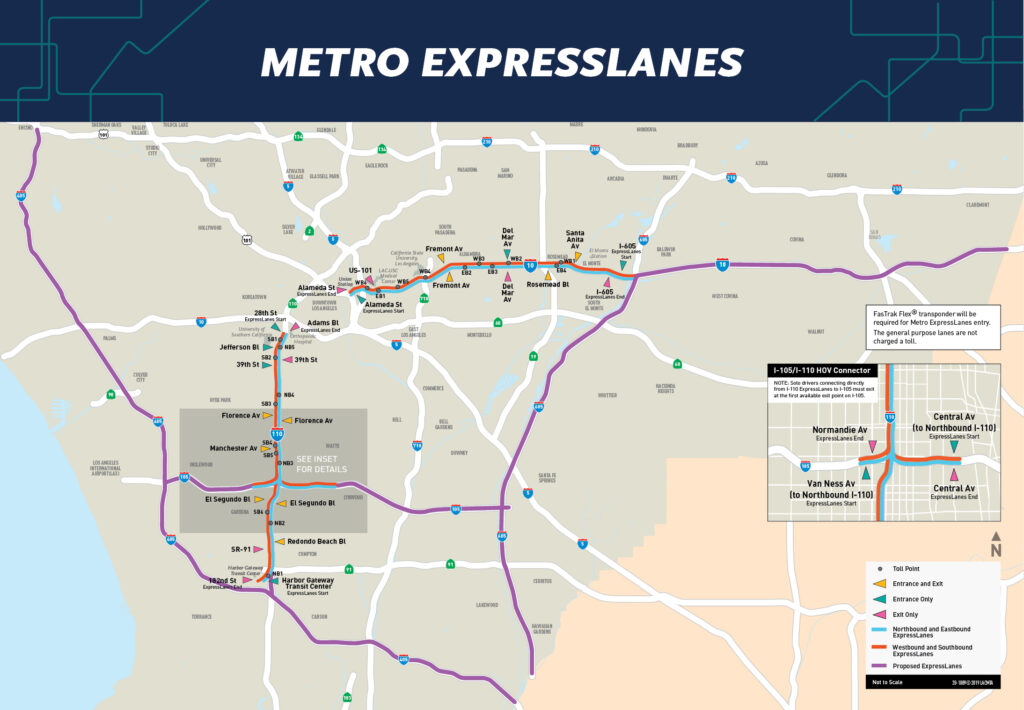

A quirk of this is the conversion of some of those HOV lanes into a number of toll lanes, referred to in some places as High Occupancy Toll (HOT), express lanes, or managed lanes. Several of those are great ways to dodge the word toll. There are different regional agencies that operate under the toll collection brand of FasTrak.

FasTrak lets everyone have their cake and eat it too. The freeway stays “free” but the HOV lane is usually expanded and repurposed to allow for vehicles with transponders to use the lane, and be charged a dynamic, demand-based fee. Depending on the time of day, and occupancy of the vehicle, it could be $0. Buses also use these lanes, and even have very bus-rider-hostile transportation centers shoved in the middle with their own entrances and exits that cars should not enter or exit.

Two-Dimensional Thinking

However, this means there are now lanes of fast moving traffic on the inside of a freeway that need to enter and exit past all the people not using these lanes. Also some of these older freeways have a lot built up around them so they can’t always expand their lanes, which means some sections are elevated above the regular traffic. To enter, or exit, the lanes you must either be in a section of the freeway where all lanes are at the same elevation, and a break in the lanes allows for merging, or there must be a grade-separated flyover to allow direct entry and exit from the lanes.

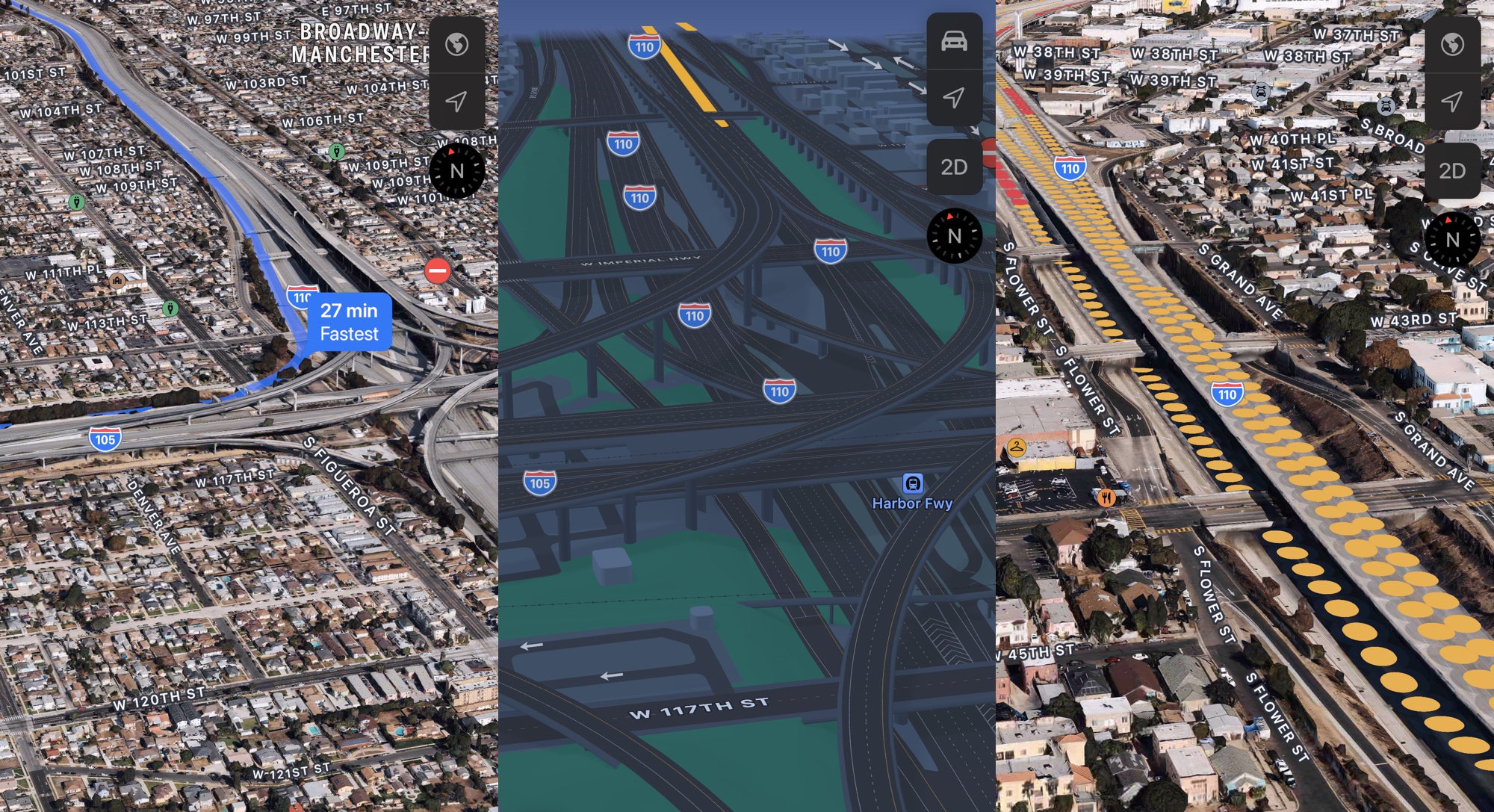

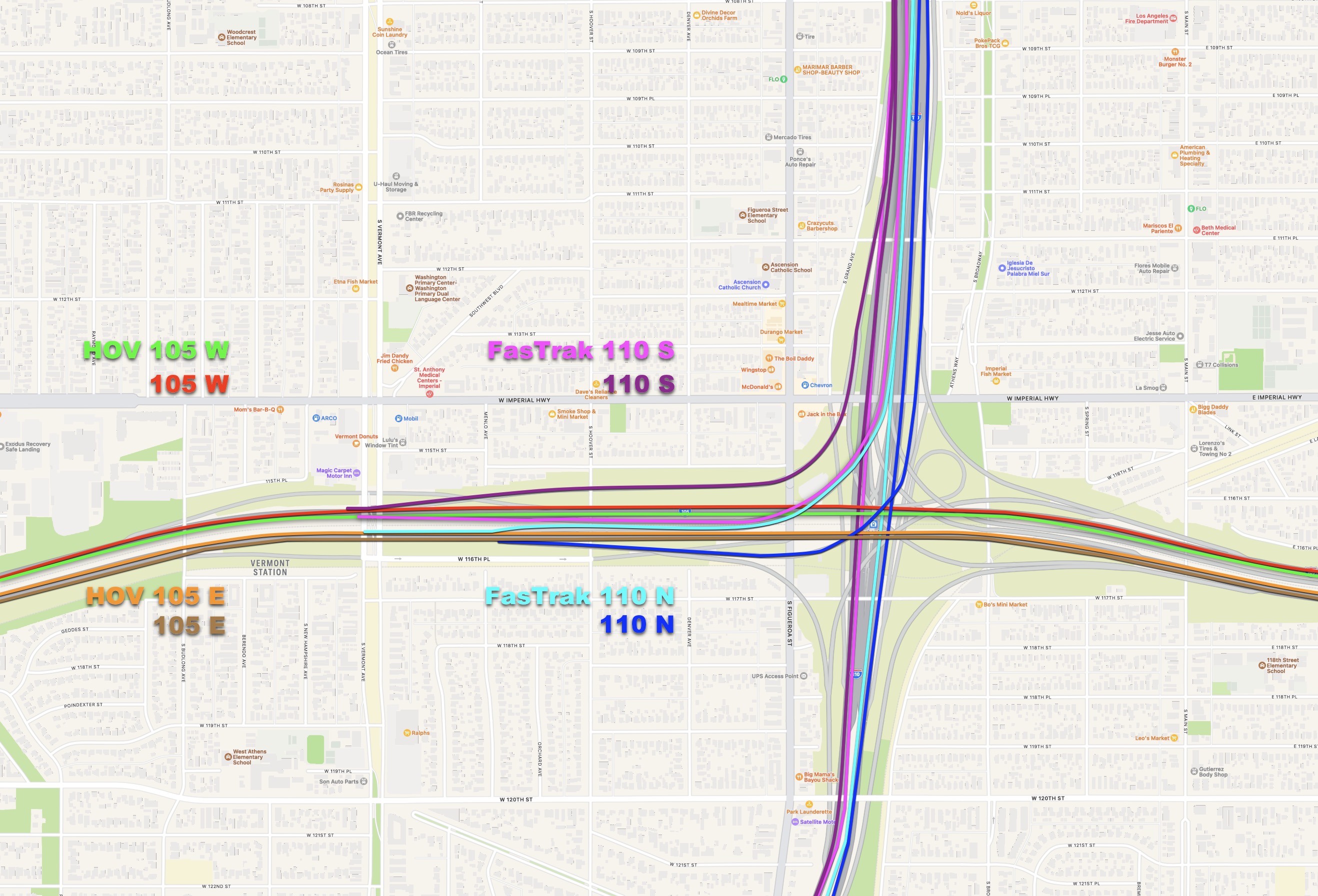

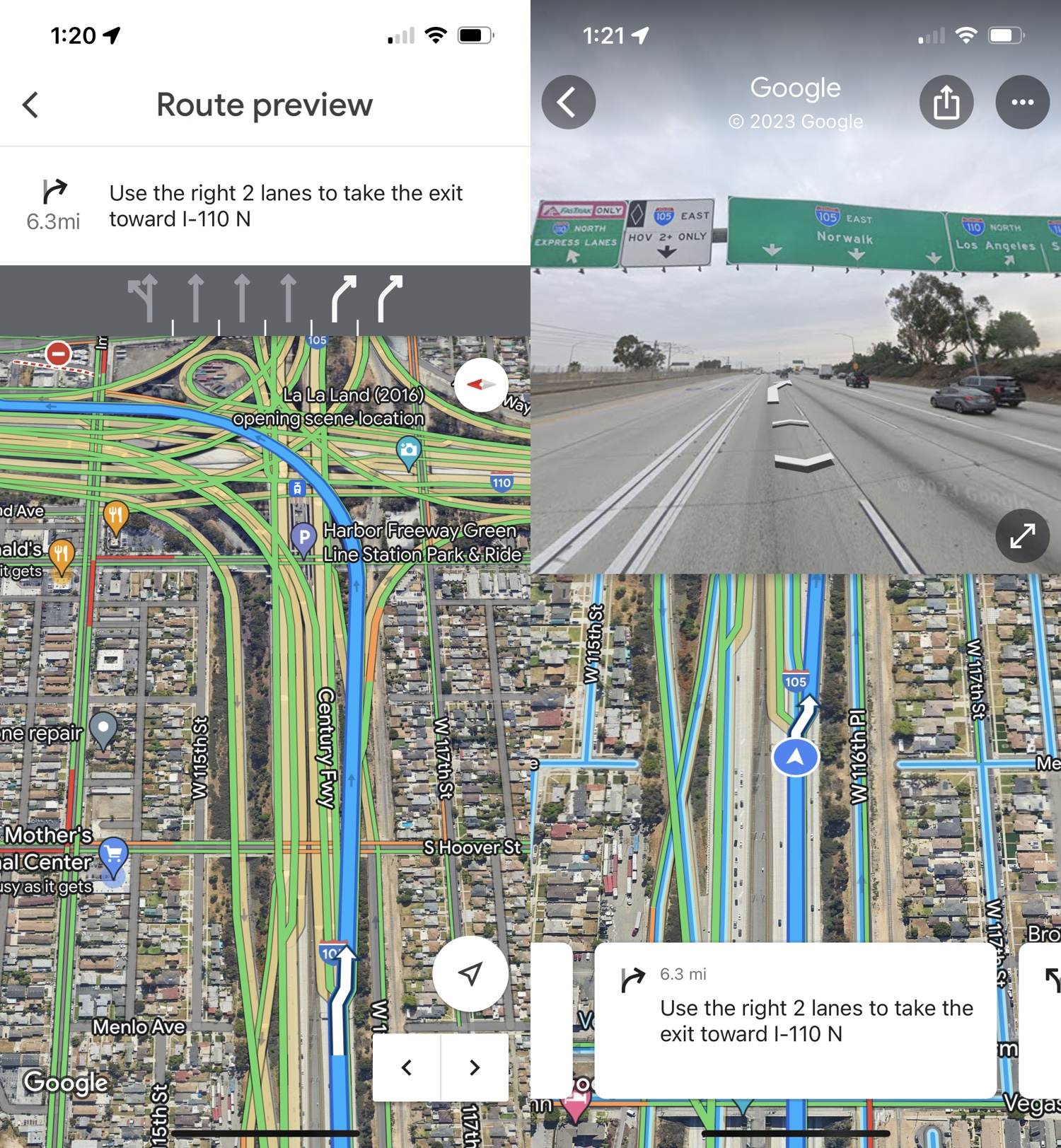

All of this stuff is visible in Apple Maps, and Google Maps. You can even see these complex interchanges in 3D in Apple Maps, or tap right along the route in Google Street View. Marvel at the volume of data collected about, but not applied to, this problem.

That is the 110-105 interchange in Los Angeles, which is a good example of every kind of lane connection possible. It is a monstrosity, but we’re not debating whether or not it should exist, it’s there, and it’s been there since the 90s, with the HOV/busway converted to FasTrak in 2012.

Now it’s time to engage in every Californians favorite pass time, talking about roads that connect to other roads. If someone is heading South on the 110 to travel from Pasadena, East Los Angeles, or Downtown Los Angeles they can enter FasTrak lanes just south of Downtown. Those two left lanes then travel in several elevated sections above the rest of the 110 traffic without any flyovers, and only a couple spots where the elevation changes to allow for merging in or out. When the 110 meets the 105 the FasTrak lane splits in two, with one lane for the 105 heading toward LAX, and the other continuing to other overpasses to go East to Norwalk, or continue South towards San Pedro.

Let’s say, theoretically, that you’re by yourself, in a car with a FasTrak transponder heading from Downtown LA to LAX, which means taking the 110 S FasTrak lane. You enter the FasTrak lane, and receive no objections from Google. Then it tells you to exit right to get on the 105 W, but the signs say to stay in the leftmost lane for the 105 W and LAX. You dutifully ignore your navigation app, and it tries to urgently reroute you as you arc across every other possible lane of transportation layered in that spot. The apps assume that you have logically fallen hundreds of feet through the air to one of the many other roads, Blues Brothers style, and then fallen over, and over again.

It eventually stops freaking out once the flyover has fully merged with the 105 W, because you’re oriented with the 105 W, but that lane is a HOV 2+ lane, because the 105 is not FasTrak. There are signs that “FasTrak must exit” so your single-occupancy vehicle needs to do that immediately. That’s not a big deal, because you should be reading traffic signs, but it should be something a navigation app can remind you off, just as it reminds you of any other lane change.

If you are traveling in the reverse direction, eastbound from LAX and northbound to Downtown LA, then your single occupancy vehicle will be in the flow of regular traffic and you will be directed to the right lane to exit for the 110 N. Unless you ignore the navigation, read the signs, and enter the HOV 2+ lanes to use the flyover from the leftmost lane. Of course attempts will be made to reroute you as you get a lovely view of the Downtown skyline, and eventually settle into the FasTrak lane of the 110 N.

If you were in that same 105 E HOV 2+ lane, with two passengers, and no transponder, heading from LAX to Downtown LA you would need to exit the HOV lane and merge on to the 110 N at the right. If you stayed in that HOV 2+ left lane because you didn’t understand the signage, you would be dumped into the FasTrak lane that requires a transponder.

I’ll leave it at just those examples, because you get the idea. These paricular lanes have been like this for over a decade. Other lanes like this exist elsewhere throughout the state, and more are being completed right this very minute.

Apple and Google are totally clueless about these lanes, which is bizarre when you can see them represented in maps, satellite views, Street View — everything.

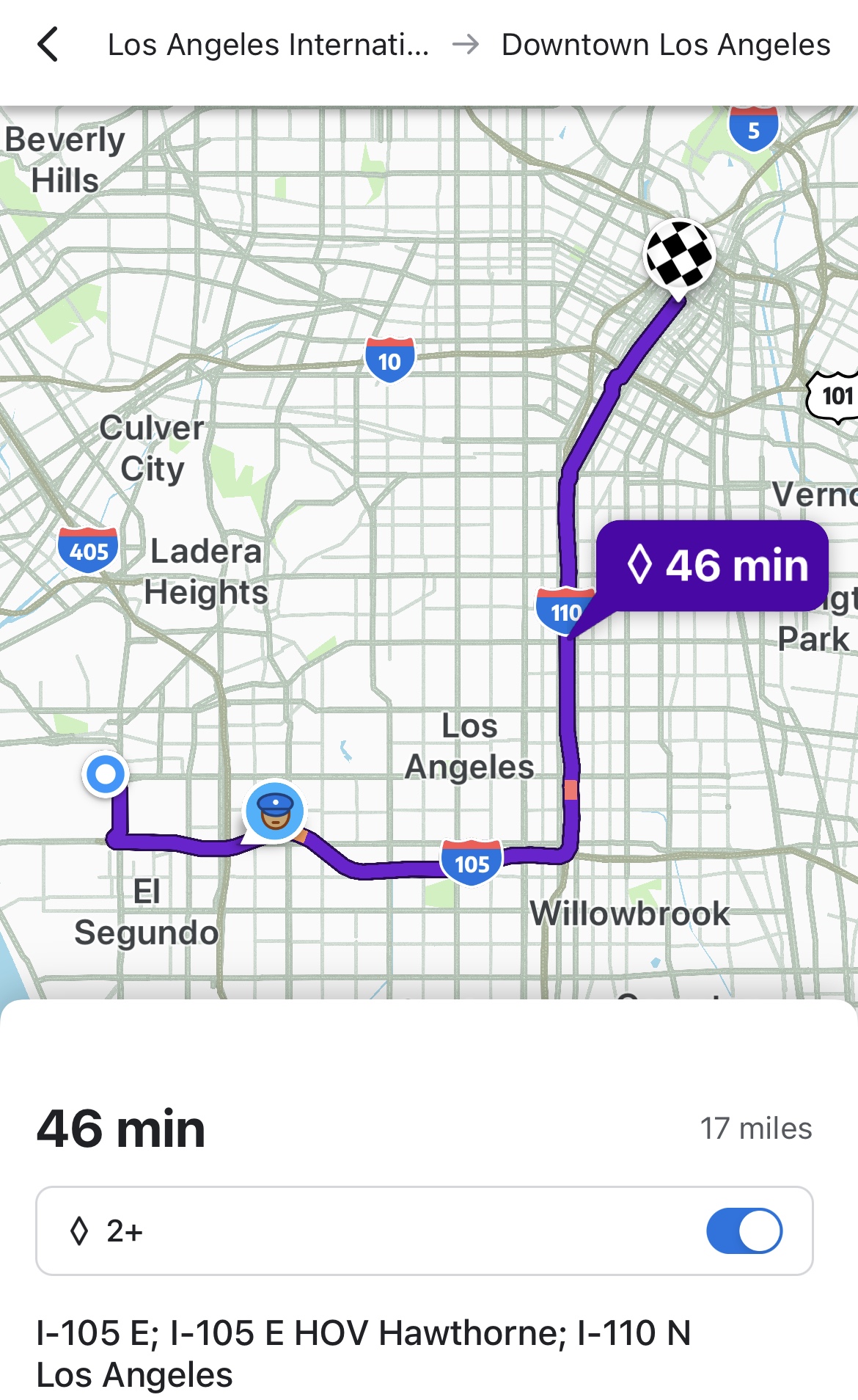

Waze, which is owned by Google, added a “HOV 2+” toggle when it shows you a suggested route with HOV 2+ lanes. This is a mixed bag, because they don’t differentiate between FasTrak and HOV 2+. So no information is presented about transponders, or other rules. Remember that a vehicle could be crossing into and out of various requirements along a route, and that HOV 2+ is an over simplification that could lead to bad directions.

The lack of proper routing extends beyond the directions alone, because it means there’s no accurate representation of the flow of traffic. You’ll notice in some of the screenshots above that Traffic data is drawn on the elevated sections of the road, but that traffic data is from the part of the freeway below.

Generally, when my boyfriend and I take certain FasTrak lanes, we know it can shave at least 10 minutes off of the route a route estimate, or more. However, if the traffic is extremely heavy the route may not be suggested at all, because there’s no understanding that we’ll be bypassing the flow of the stopped traffic. We can trick it sometimes by changing our start, end, or adding a middle position that puts us specifically on a route to see why it’s not recommended, but that still relies on our knowledge, and hunches about things. You’re also assuming the FasTrak lane is completely unaffected by the traffic, which is not always true. That’s not really want you want in the mapping applications from two of the most powerful companies in the world, who just so happen to be in the same state as you.

I know that from a user interface perspective anything added to the interface makes it less clean, and straight-forward to use, so there’s no simple suggestion of “just put toggles in for everything.” However, the reality of different kinds of traffic regulation — whether that’s occupancy, transponders, box trucks, or other forms of traffic control — isn’t going away. Our phones are integral to transportation, so maybe someday, in the far future, we’ll have ways to manage electronic toll collection through them, and then it could all become a part of the navigation process itself.

Both Apple and Google need to tackle this problem in a way that helps their navigation apps perform better, especially when Apple is working on whatever that misguided car thing is, and Google is working on being the infotainment backbone of the automotive industry.

At the very least, they can do better for The Californians.

Category: text