Rumored Apple TV Rumored to Not Have Rumored 4K

There was a piece by John Paczkowski, the managing editor of BuzzFeed San Francisco about the new Apple TV not supporting 4K. This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone, really, because the current one doesn’t support it, and the only two streaming media companies that offer 4K (UHD) content are Netflix (some original programming) and YouTube (some user-generated videos). iTunes doesn’t sell UHD content to use on your Retina Macs, and Netflix won’t even stream UHD to them. Maybe save UHD for some point in the future when there’s more than 6 things to watch in UHD? When it can be a real, headline feature?

Naturally, John concludes his post with that acknowledgment. Actually he concludes with “Apple declined to comment ‘on rumor and speculation.’“

SD to HD to UHD

A few days ago, my boyfriend and I were watching a rerun of Friends on the TV Land channel. It was an episode that was remastered in HD, compressed by DirecTV, and displayed in his living room. I had seen the episode a long time ago, it was one where Phoebe’s identical twin sister, Ursula, was using Phoebe’s name. Phoebe confronts Ursula over it. Lisa Kudrow has no real life twin, so this was accomplished with split screen, and doubles. The shots showing the back of the double, and Lisa Kudrow’s face were as crisp as anything in HD on DirecTV. The split screen shots, where Lisa Kudrow was composited with herself, were a fuzzy mess. It kept cutting back and forth from crisp shots, to blurry shots, as the scene played out. To my trained eye, it looked like whoever was in charge of remastering Friends had to blow up the original standard definition output and crop it, instead of going back to the source and redoing the split screen. Remember it’s not just scaling, it’s also the aspect ratio change so you actually have to remove pixels on top and bottom.

Ultimately, it’s Friends, so very few people will care about a handful of blurry shots. This does illustrate a problem with “content” in that it isn’t future proof. Companies either can’t (original source is gone, or degraded) or won’t ($) remaster visual effects shots when they transition from one output medium to another. Naturally, most people assume that’s an issue for Star Trek and Babylon 5 (and it is), but it’s also a problem for Friends, and other sitcoms. Even dramatic shows that take place in the real world make extensive use of enhancement. Set extensions, painting out wires, adding explosions, combining different takes, image stabilization — all kinds of stuff that people don’t even perceive. Only they will perceive them because they’ll all be blurry when that moves up to a higher resolution.

Networks are still converting shows to HD, notably HBO’s The Wire and notoriously Fox’s Buffy: The Vampire Slayer.

Even CBS, which has been applauded for their work remastering the original Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation, has no immediate desire to remaster Star Trek: Deep Space Nine or Star Trek: Voyager. (My personal theory is that this has to do with the decline of Blu-Ray sales, in general, reducing the profit.)

Babylon 5 a show that used computer graphics instead of miniature photography, is adrift. Warner Bros. lost everything they had. Jason Snell referred me to a fan that tried to redo all the effects himself (he gave up).

HD is still the law of the land in TV. It is newsworthy for a production to work in a resolution higher than HD. Netflix’s House of Cards is being mastered in 6K (and archived) and also mastered for UHD (4k), and HD, to be streamed today. Keep in mind, 6K isn’t even a standard, the next step up right now is 8K UHD, so … Let’s see where that goes?

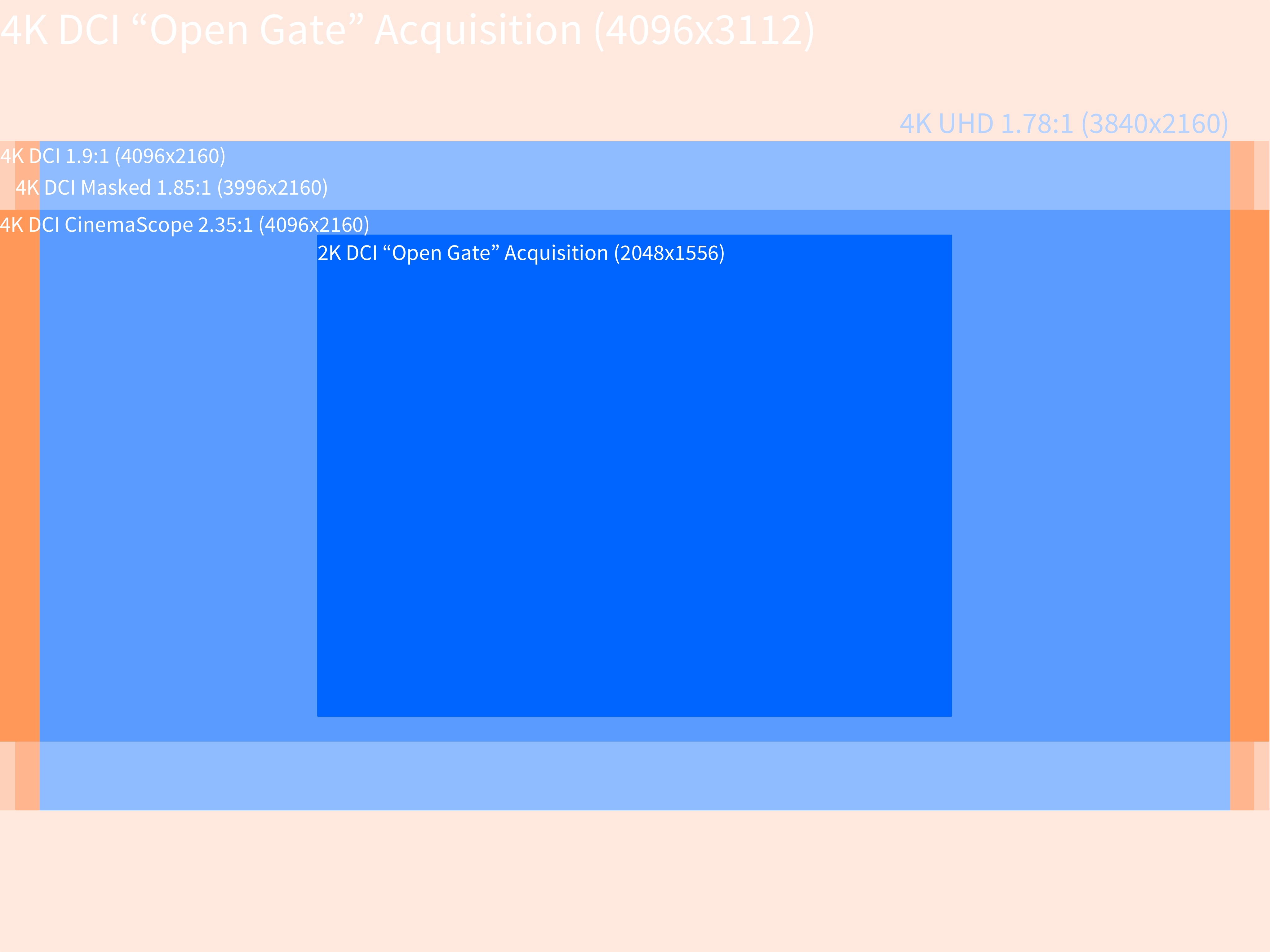

Films are in the same boat. Most VFX have been produced at 2K. The exact resolution varies based on the project, and what the client requires for delivery, but it’s around 2048 wide with different regions of the frame being masked to produce different aspect ratios (or using anamorphic lenses that compress and stretch horizontally). Film resolutions and TV resolutions are not directly comparable so “4K” doesn’t mean the same thing.

Even films like the original Star Wars trilogy have 4K problems. A firm called NanoTech Entertainment hired Petr Harmy, the creator of the unauthorized Star Wars Despecialized Edition HD remasters to do the same thing in 4K for their UltraFlix 4K streaming service. Think of how many times Star Wars has been futzed with — whether George Lucas was involved or not.

Even knowing 4K will be eventually asked for, modern motion pictures aren’t entirely produced in 4K DCI (around 4096 wide). Those that are, might include VFX shots done at 2K, and blown-up to 4K.

This creates an uneven library of material to pull from and populate your “4K” TV with.

It’s OK, Netflix, your ISP, Vimeo, YouTube, DirecTV, Verizon, etc. can all step in and compress a video too, so it’s not like you’re literally getting pixel-per-pixel stuff anyway.

Colorspace, The Final Frontier

Beyond the issues of pixels, is colorspace. An overly simple way to think of that is the way the color data is stored, but it also has to do with how that stored data is transformed on to the screen where you see it. The internet is just awful when it comes to color accuracy. That has to do with the delightful interplay between how images and video are stored, the browser, plugins, operating systems, drivers, and monitors. Line up a bunch of computers and load the same sites on all of them and you will see slight differences. This is also why the colorspaces you’ll see used most often are sRGB, or Adobe RGB, because they’re from so long ago, and use such a narrow gamut, that maybe you’ll luck out and it’ll look uniformly bland.

As bad as that is, your home TV is weirder. HD TVs support a standard colorspace called Rec 709. As anyone who’s seen more than one TV at a time can attest, it’s not uniform color. It too is subject to the whims of the TV manufacturer. Sometimes they increase the saturation, and brightness, to make their TV seem more appealing on a showroom floor.

4K UHD is also plagued with this problem. Again, it supports a standard — Rec 2020— but it suffers the same fate, with each manufacturer doing different things to how they display that Rec 2020 material in your living room.

Here’s a very thorough piece from FX Guide about colorspace, and color pipelines.

Most consumers aren’t fazed by this at all because they simply don’t care. Much like they don’t care about resolution issues. They want their whole TV filled with an image. They want to know they bought the highest number of pixels, and they want it to be bright and colorful. Mark my words, in a few years, some manufacturer is going to make some Android stunt-phone that’ll claim to show 4K movies and TV shows, and they’ll get all the positive press in the world, because numbers are bigger than other numbers.

Everything’s a lie.

Category: text